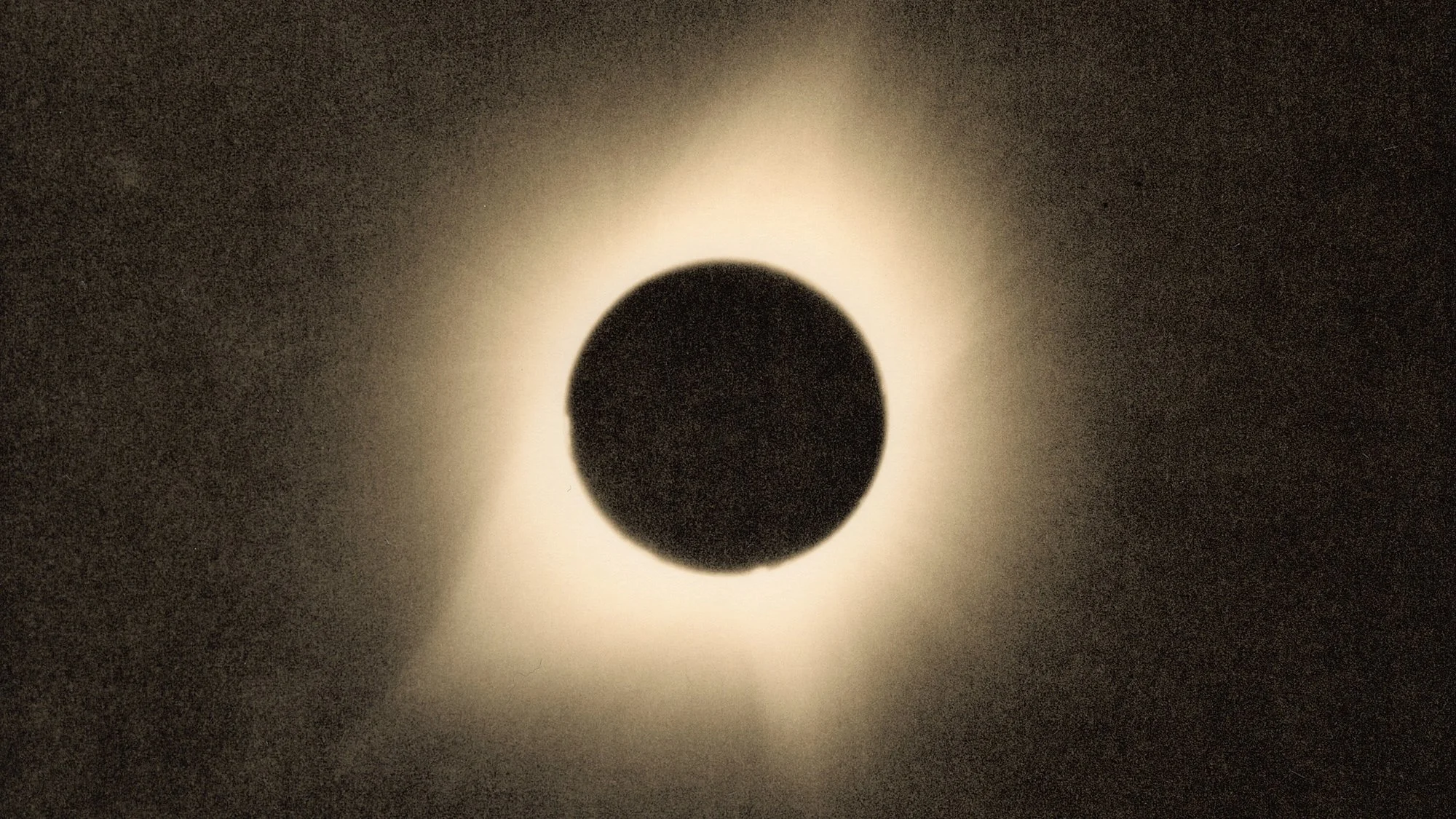

eclipse

If you find yourself in the unfortunate position of photographing a solar eclipse on medium-format film, you can be fairly leisurely about shooting the sun in its partial phases. The totality, however, is another story. You have about two short minutes to frame and capture whatever you can, while your mind is being blown and people are shouting, laughing and howling around you. The diamond ring, with that stunning sparkle and flare, lasts about a second. No one can tell you the proper exposure beforehand, and your camera’s meter is worthless. No time for bracketing exposures, no room for error.

After undertaking this masochistic project myself – including about four days of prep and testing beforehand – seeing those beautiful negatives was one of my great days at the lab.

Back in the darkroom, I knew I wanted to make lith prints. The lith process produces painterly tones and gradations that vary from print to print, with grain structure, hues and contrast both lovely and unpredictable. It requires photo papers that are no longer made, so I’ve been buying certain discontinued ones off eBay for years. Lith printing uses an alternative mix of chemicals in the darkroom, with each print taking 20 to 60 minutes to expose, develop and finish. The prints are unique little gems, delicate and temperamental and fast-changing in the chemistry. Their emergence in the developer gets halted at a subjective point that changes from print to print. There’s no formula, no rules. And no two prints are exactly alike.